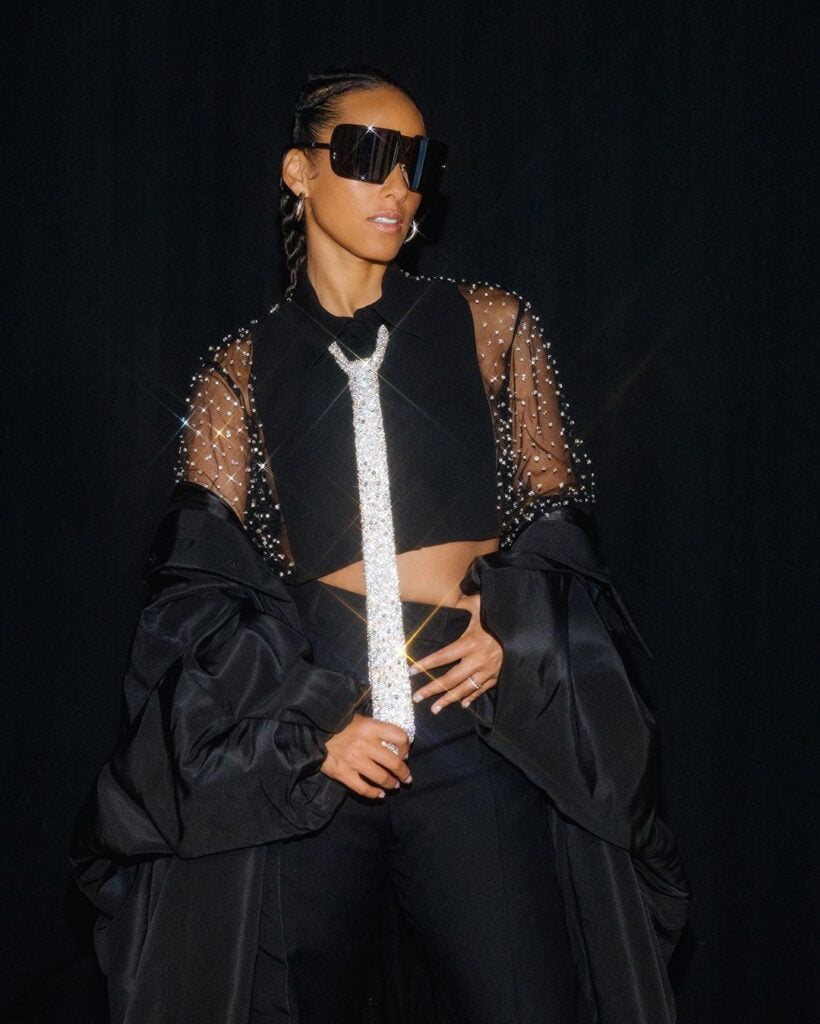

ALICIA KEYS

Alicia Augello Cook (born January 25, 1980), known professionally as Alicia Keys, is an American singer-songwriter. A classically trained pianist, Keys started composing songs when she was 12 and was signed at 15 years old by Columbia Records. After disputes with the label, she signed with Arista Records and later released her debut album, Songs in A Minor, with J Records in 2001. The album was critically and commercially successful, selling over 12 million copies worldwide. It spawned the Billboard Hot 100 number-one single “Fallin'”, and earned Keys five Grammy Awards in 2002. Her second album, The Diary of Alicia Keys (2003), was also a critical and commercial success, selling eight million copies worldwide, and producing the singles “You Don’t Know My Name”, “If I Ain’t Got You”, and “Diary”. The album garnered her an additional four Grammy Awards.

In 2004, her duet “My Boo” with Usher became her second number-one single. Keys released her first live album, Unplugged (2005), and became the first woman to have an MTV Unplugged album debut at number one. Her third album, As I Am (2007), sold seven million copies worldwide and produced the Hot 100 number-one single “No One”. In 2007, Keys made her film debut in the action-thriller film Smokin’ Aces. She released the theme song to the James Bond film Quantum of Solace “Another Way to Die” with Jack White. Her fourth album, The Element of Freedom (2009), became her first chart-topping album in the United Kingdom, and sold four million copies worldwide. The album included the Billboard Hot 100 charting singles “Doesn’t Mean Anything”, “Try Sleeping with a Broken Heart”, “Un-Thinkable (I’m Ready)”. Keys’ collaboration with Jay-Z on “Empire State of Mind” (2009), became her fourth number-one single in the United States. Her fifth album Girl on Fire (2012), became her fifth Billboard 200 topping album, and included the successful title track. Her sixth studio album, Here (2016), became her seventh US R&B/Hip-Hop chart-topping album. Her seventh and eighth studio albums, Alicia (2020) and Keys (2021), spawned the singles “Show Me Love”, “Underdog”, “Lala” and “Best of Me”. She released Santa Baby, her ninth studio album, in 2022 under her independent label, Alicia Keys Records.

Keys has sold over 90 million records worldwide, making her one of the world’s best-selling music artists. She was named by Billboard as the R&B/Hip-Hop Artist of the Decade (2000s); and placed tenth on their list of Top 50 R&B/Hip-Hop Artists of the Past 25 Years. She has received numerous accolades in her career, including 15 Grammy Awards, 17 NAACP Image Awards, 12 ASCAP Awards, and an award from the Songwriters Hall of Fame and National Music Publishers Association. VH1 included her on their 100 Greatest Artists of All Time and 100 Greatest Women in Music lists, while Time has named her in their 100 list of most influential people in 2005 and 2017. Keys is also acclaimed for her humanitarian work, philanthropy, and activism, e.g. being awarded Ambassador of Conscience by Amnesty International; she co-founded and serves as the Global Ambassador of the nonprofit HIV/AIDS-fighting organization Keep a Child Alive.

In 1994, manager Jeff Robinson met 13-year old Keys, who participated in his brother’s youth organization called Teens in Motion. Robinson’s brother had been giving Keys vocal lessons in Harlem. His brother had talked to him about Keys and advised him to go see her, but Robinson shrugged it off as he had “heard that story 1,000 times”. At the time, Keys was part of a three-member band that had formed in the Bronx and was performing in Harlem. Robinson eventually agreed to his brother’s request, and went to see Keys perform with her group at the Police Athletic League center in Harlem. He was soon taken by Keys, her soulful singing, playing contemporary and classical music and performing her own songs. Robinson was excited by audiences’ reactions to her. Impressed by her talents, charisma, image, and maturity, Robinson considered her to be the “total package”, and took her under his wing. By this time, Keys had already written two of the songs that she would later include on her debut album, “Butterflyz” and “The Life”.

Robinson wanted Keys to be informed and prepared for the music industry, so he took her everywhere with him, including all the meetings with attorneys and negotiations with record labels, while the teenager often became disgruntled with the process. Robinson had urged Keys to pursue a solo career, as she remained reluctant, preferring the musical interactions of a group. She took Robinson’s advice after her group disbanded, and contacted Robinson who in 1995 introduced her to A&R executive Peter Edge.

Robinson and Edge helped Keys assemble some demos of songs she had written and set up a showcases for label executives. Keys performed on the piano for executives of various labels, and a bidding war ensued. Edge was keen to sign Keys himself but was unable to do so at that time due to being on the verge of leaving his present record company, Warner Bros. Records, to work at Clive Davis’ Arista Records. During this period, Columbia Records had approached Keys for a record deal, offering her a $26,000 white baby grand piano; after negotiations with her and her manager, she signed to the label, at age 15. Keys was also finishing high school, and her academic success had provided her opportunity for scholarship and early admission to university. That year, Keys accepted a scholarship to study at Columbia University in Manhattan. She graduated from high school early as valedictorian, at the age of 16, and began attending Columbia University at that age while working on her music. Keys attempted to manage a difficult schedule between university and working in the studio into the morning, compounding stress and a distant relationship with her mother. She often stayed away from home, and wrote some of the most “depressing” poems of her life during this period. Keys decided to drop out of college after a month to pursue music full-time.

Columbia Records had recruited a team of songwriters, producers and stylists to work on Keys and her music. They wanted Keys to submit to their creative and image decisions. Keys said they were not receptive to her contributions and being a musician and music creator. While Keys worked on her songs, Columbia executives attempted to change her material; they wanted her to sing and have others create the music, forcing big-name producers on her who demanded she also write with people with whom she was not comfortable. She would go into sessions already prepared with music she had composed, but the label would dismiss her work in favor of their vision. “It was a constant battle, it was a lot of -isms”, Keys recalled. “There was the sexism, but it was more the ageism – you’re too young, how could you possibly know what you want to do? – and oh God, that just irked me to death, I hated that.” “The music coming out was very disappointing”, she recalled. “You have this desire to have something good, and you have thoughts and ideas, but when you finish the music it’s shit, and it keeps on going like that.” Keys would be in “perpetual music industry purgatory” under Columbia, while they ultimately “relegated [her] to the shelf”. She had performed “Little Drummer Girl” for So So Def’s Christmas compilation in 1996, and later co-wrote the song “Dah Dee Dah (Sexy Thing)” for the Men in Black (1997) film soundtrack, the only released recording Keys made with Columbia.

Keys “hated” the experience of writing with the people Columbia brought in. “I remember driving to the studio one day with dread in my chest”, she recalled. Keys said the producers would also sexually proposition her. “It’s all over the place. And it’s crazy. And it’s very difficult to understand and handle”, she said. Keys had already built a “protect yourself” mentality from growing up in Hell’s Kitchen, which served her as a young teen then in the industry having to rebuff the advances of producers and being around people who “just wanted to use [her]”. Keys felt like she could not show weakness. Executives at Columbia also wanted to manufacture her image, with her “hair blown out and flowing”, short dresses, and asking her to lose weight; “they wanted me to be the same as everyone else”, Keys felt. “I had horrible experiences,” she recalled. “They were so disrespectful … I started figuring, ‘Hey, nothing’s worth all this.'” As months passed, Keys had grown more frustrated and depressed with the situation, while the label requested the finished tracks. Keys recalled, “it was around that time that I realized that I couldn’t do it with other people. I had to do it more with myself, with the people that I felt comfortable with or by myself with my piano.” Keys decided to sit in with some producers and engineers to ask questions and watch them technically work on other artists’ music.[38] “The only way it would sound like anything I would be remotely proud of is if I did it”, Keys determined. “I already knew my way around the keyboard, so that was an advantage. And the rest was watching people work on other artists and watching how they layer things”.

Her partner Kerry “Krucial” Brothers suggested to Keys she buy her own equipment and record on her own. Keys began working separately from the label, exploring more production and engineering on her own with her own equipment. She had moved out of her mother’s apartment and into a sixth-floor walk-up apartment in Harlem with Brothers, where she fit a recording studio into their bedroom and worked on her music. Keys felt being on her own was “necessary” for her sanity. She was “going through a lot” with herself and with her mother, and she “needed the space”; “I needed to have my own thoughts, to do my own thing.” Keys and Brothers later moved to Queens and together they turned the basement into KrucialKeys Studios. Keys would return to her mother’s house periodically, particularly when she felt “lost or unbalanced or alone”. “She would probably be working and I would sit at the piano”, she reminisced. During this time, she composed the song “Troubles”, which started as “a conversation with God”, working on it further in Harlem. Around this time the album “started coming together”, and she composed and recorded most of the songs that would appear on her album. “Finally, I knew how to structure my feelings into something that made sense, something that can translate to people”, Keys recalled. “That was a changing point. My confidence was up, way up. The different experience reinvigorated Keys and her music. While the album was nearly completed, Columbia’s management changed and more creative differences emerged with the new executives. Keys brought her songs to the executives, who rejected her work, saying it “sounded like one long demo”. They wanted Keys to sing over loops, and told Keys they will bring in a “top” team and get her “a more radio-friendly sound”. Keys would not allow it; “they already had set the monster loose”, she recalled. “Once I started producing my own stuff there wasn’t any going back.” Keys stated that Columbia had the “wrong vision” for her. “They didn’t want me to be an individual, didn’t really care”, Keys concluded. “They just wanted to put me in a box.” Control over her creative process was “everything” to Keys.

Keys had wanted to leave Columbia since they began “completely disrespecting [her] musical creativity”. Leaving Columbia was “a hell of a fight”, she recalled. “Out of spite, they were threatening to keep everything I’d created even though they hated it. I thought I’d have to start over again just to get out, but I didn’t care.” Keys said in 2001: “It’s been one trial, one test of confidence and faith after the next.” To Keys, “success doesn’t just mean that I’m the singer, and you give me my 14 points, and that’s all. That’s not how it’s going to go down.” Edge, who was by that time head of A&R at Arista Records, said, “I didn’t see that there was much hands-on development at Columbia, and she was smart enough to figure that out and to ask to be released from her contract, which was a bold move for a new artist.” Edge introduced Keys to Arista’s then-president, Clive Davis, in 1998.