AFFILIATES

To Join KONTA TELEVISION and become an exclusive affiliate, kindly submit your creative video and send a hard copy to our Affiliate address and one of our specialized personnel will contact you within 3 days of receipt.

Please fill out the form below and our new talent music specialists will review your video and contact you.

To Join KONTA TELEVISION and become an exclusive affiliate, kindly submit your creative video and send a hard copy to our Affiliate address and one of our specialized personnel will contact you within 3 days of receipt. Please fill out the form below and our new talent music specialists will review your video and contact you

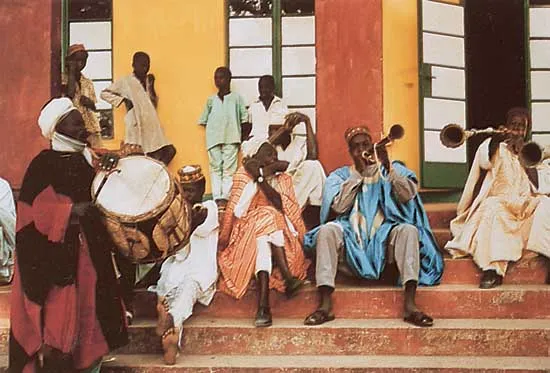

African Music History

It is widely acknowledged that African music has undergone frequent and decisive changes throughout the centuries. What is termed traditional music today is probably very different from African music in former times. Nor has African music in the past been rigidly linked to specific ethnic groups. The individual musician, his style and creativity, have always played an important role.

The material sources for the study of African music history include archaeological and other objects, pictorial sources (rock paintings, petroglyphs, book illustrations, drawings, paintings), oral historical sources, written sources (travelers’ accounts, field notes, inscriptions in Arabic and in African and European languages), musical notations, sound recordings, photographs and motion pictures, and videotape.

In ancient times the musical cultures of sub-Saharan Africa extended into North Africa. Between circa 8000 and 3000 BC, climatic changes in the Sahara, with a marked wet trend, extended the flora and fauna of the savanna into the southern Sahara and its central highlands.

During this period, human occupation of the Sahara greatly increased, and, along rivers and small lakes, Neolithic, or New Stone Age, cultures with a so-called aquatic lifestyle extended from the western Sahara into the Nile River valley.

The aquatic cultures began to break up gradually between 5000 and 3000 BC, once the peak of the wet period had passed. The wet climate became more and more restricted to shrunken lakes and rivers and, to a greater extent, to the region of the upper Nile. Today remnants survive perhaps in the Lake Chad area and in the Nile swamps.

The cultures of the “Green Sahara” left behind a vast gallery of iconographic documents in the form of rock paintings, among which are some of the earliest internal sources on African music. One is a vivid dance scene discovered in 1956 by the French ethnologist Henri Lhote in the Tassili-n-Ajjer plateau of Algeria.

Attributed on stylistic grounds to the Saharan period of the Neolithic hunters (c. 6000–4000 BC), this painting is probably one of the oldest extant testimonies to music and dance in Africa. The body adornment and movement style are reminiscent of dance styles still found in many African societies.

Some of the earliest sources on African music are archaeological. Although musical instruments made of vegetable materials have not survived in the deposits of sub-Saharan climatic zones, archaeological source material on Nigerian music has been supplied by the representations of musical instruments on stone or terra-cotta from Ife, Yorubaland.

These representations show considerable agreement with traditional accounts of their origins. From the 10th to the 14th century AD, ig̀bìn drums (a set of footed cylindrical drums) seem to have been used.

The dùndún pressure drum, now associated with Yoruba culture and known in a broad belt across the savanna region, may have been introduced around the 15th century, since it appears in plaques made during that period.

Musical instruments

Outsiders have often overlooked the enormous variety of musical instruments in Africa in the mistaken belief that Africans play only drums.

Yet even Hanno the Carthaginian, who recorded a brief visit to the west coast of Africa in the 5th century BCE during a naval expedition, noted wind instruments as well as percussion. Of an island within the gulf of “Hesperon Keras,” he wrote:

By day we saw nothing but woods, but by night we saw many fires burning, and heard the sound of flutes and cymbals, and the beating of drums, and an immense shouting. Fear therefore seized on us, and the soothsayers bid us quit the island.

Ensembles fitting this description may be found over a wide area of West Africa today, serving as accompaniment to dancing and merrymaking or as an essential ingredient of ceremonial or cultic activities.

Besides the percussion and wind instruments noted by Hanno, there are also stringed instruments of many kinds, ranging from the simple mouth bow to more complex varieties of zithers, harps, lutes, and lyres.

While the aggregate of instrumental resources distributed over the continent is vast, each society tends to specialize in a limited assortment, and there is a wide variety from region to region.

In some areas interesting new hybrid varieties emerged in the 20th century in response to outside influence, notably the endingidi spike fiddle of Uganda, malipenga gourd kazoos of Tanzania and Malawi, and chordophones such as the ramkie and segankuru of South Africa.

Musical instruments in African societies serve a variety of roles. Some instruments may be confined to religious or cultic rituals or to social occasions.

Among some peoples there may also be restrictions as to the age, sex, or social status of the player.

Among the Xhosa, for example, only girls play the imported jew’s harp, a modern replacement for the traditional mouth bow, which was formerly their prerogative.

Besides recreational applications, or as accompaniment for dancing, instruments may serve many other roles. In Lesotho it is claimed that cattle graze more contentedly when entertained by the sound of the lesiba mouth bow.

Among the Shona in Zimbabwe, a local form of lamellaphone known as likembe dza vadzimu serves in rituals of ancestor worship, while in the kingdom of Buganda the royal drums formerly held higher status than the king.

In West and central Africa, pressure drums may serve for the transmission of messages or, together with trumpets, for the declamation of praises, by mimicking the tonal and rhythmic patterns of speech.

All sub-Saharan languages (except Swahili) are “tone languages,” in the sense that the meaning of words depends on the tone or pitch in which they are said.

Consequently, instrumental music—or even natural sounds such as birdsong—often imitates or suggests meaningful phrases of the spoken language.

Sometimes this is intentional and sometimes it is merely fortuitous, but in either case it escapes the notice of uninformed outsiders.

Certain instruments are used solely for song accompaniment. Here the interplay between voice and instrument is often intricate and delicately balanced. Zulu solo songs, in earlier times, were often self-accompanied on the ugubhu gourd bow.

In such bow songs, while the instrumental melody was influenced by the tone requirements of the song’s lyrics, the tuning of the bow determined the vocal scale to which the singer conformed.

Today when Zulus use the modern Western guitar, precisely the same antiphonal relationship and mutual interdependence between voice and instrument is maintained.

The following is a brief sampling of the principal instruments found in Africa.

Idiophones

In this class the substance of the instrument itself, owing to its solidity and elasticity, yields sound without requiring strings or stretched membranes. Some are sounded by striking, others by shaking, scraping, plucking, or friction. Idiophones are numerous and widely distributed throughout the continent. On musical grounds, they may be divided into instruments used mainly for rhythm and several varieties tuned and used melodically.

Castanets

The castanet stems from the Mediterranean, although it originated in Phoenicia in about 1000 BC. This idiophone musical instrument comes with two hollowed-out shells, bones, or ivory held together by a rope. You can play castanets by inserting the loops through your thumb and then using your other fingers to close and hit the shells together.

Musicians play the castanets in pairs. The right castanet is called hembra, while the left one is referred to as macho. You can play both in the same beat or have one (the macho) for rhythm.

Chimes

Chimes are also part of this idiophone instruments list, and it’s perhaps the most common. You will find it in churches, schools, offices, and other settings. In an orchestra or band, a set of chimes may hang from a block of wood or sit on a platform of wood. To create the musical vibration, the player uses a small stick with a rounded end called a mallet. A set of chimes typically includes eight-round, metal chimes with a hollow center. This provides the player with a full octave range of notes.

Cowbell

The single and double cowbells offer a hand-percussive instrument that originally aided herdsmen in tracking their flocks. Those vibrations came from a metal mallet inside the metal bell hung on a cow’s or one’s neck. Classical music initially adopted the metal bell to create a quick, single note using a separate mallet to strike the outside.

Slit Drums

Unlike other percussion, these wooden drums are drum head-free. As a matter of fact, a slit drum has a hollow sculpture with three narrow groves or slits shaped like an H. The ends of the drum are closed and typically can produce two different pitches.

Tubular Bells

Tubular bells look like chimes when they take the hanging form but typically include a two-octave range or 16 distinct tube-shaped bells. A hand percussion version also exists though that resembles a pipe twisted into an X shape with one side solid pipe. Musicians also refer to tubular bells as orchestral bells. They emit a sound similar to church bells or a carillon when struck with a mallet.

Cymbals

A cymbal may take the form of a single hollow round plate of metal or two such plates coupled so that the hollows meet. It may also attach to a rod and function as a part of a drum kit, such as rock and country band use.

There are hand-held cymbals that the player brings together to create a clashing sound. Cymbals offer a diversity, including splash cymbals, ride cymbals, crash cymbals, t-natural cymbals, etc.

Gong

Originating East and Southeast Asia, this circular, flat disk struck with a mallet, issues a loud and resounding sound. The note of a gong sounds for many counts unless stopped. These large disks hang from a supporting post. Some progressive rock bands and jazz ensembles use the gong. The instrument became famous in popular times when featured on an entertainment show called The Gong Show.

Maracas

The gourd rattle called maracas stems from South American and Latin music, especially their orchestras. Typically egg or oval in shape, the objects sealed inside create a rattling sound when shaken. The materials used within the gourds vary from beans, and stones to beads. Modern music also uses maracas crafted of leather, wood, or plant pods.

Marimba

The African musical instrument the marimba strongly resembles a xylophone. A traditional marimba uses wooden bars with a tuned calabash resonator beneath each. In Latin America, musicians adopted the design but replaced the calabash with gourds.

When crafted for use in the orchestra, this six-and-a-half-octave instrument combines wooden bars attached to a frame with tube or metal resonators beneath each bar. Some marimbas hang around the player’s waist.

Vibraphone

The musical instrument vibraphone, also known as the vibraharp or vibes, shares its shape with the xylophone. It uses metal bars and mallets covered in wool or felt to strike the metal which has a tuned, tubular resonator beneath it. Striking the metal creates a mellow tone. The resonator helps the vibraphone bars sustain the tones for long note counts.

Tambourine

From the French word for drum, tambour, the tambourine consists of a wood frame with small pieces of metal called zils. When you shake the frame, the zils hit each other and produce sound. Some tambourines also have a drum head, but others do not.

Triangle

The triangle or triangle bell was traditionally a dinner bell. And, as its name suggests, it’s a triangular-shaped idiophone instrument made from either steel or cast iron. You can play the triangle by hitting the triangle with a short metal stick.

Wood Block

Woodblock, as its name suggests, is an instrument featuring a block of wood. This common aboriginal instrument features a slit in its center and can produce sound when you hit it with a mallet. This idiophone instrument is commonly heard in Dixieland music.

Handpan

The handpan or hang drum only came into existence in 2001. This idiophone instrument uses a lenticular shape similar to a turtle shell or an upside-down wok. It creates a soft sound similar to raindrops when struck with your hand. A hole on the bottom of the handpan provides the amplitude for the deep bass note of the instrument. Although easy to play, they have yet to catch on because they cost a lot to produce.

Xylophone

You can’t conclude an idiophone instruments list without the xylophone. It features resonators beneath each wooden bar. So, when you hit this instrument with a mallet, it emits a note. This idiophone instrument typically includes more than three octaves.

Membranophones

All African drums except the slit drum fall within this class, sharing the basic feature of having a stretched animal skin as their sounding medium. The mirliton, or small “singing membrane,” is often added to the bodies of drums and xylophone resonators as a supplementary buzzing device. It is an essential component of the malipenga gourd kazoos used in Tanzania and Malawi to simulate military band music.

Africa has a wide variety of drums, which may serve in a number of different roles, some of them not primarily musical. Their manufacture is often steeped in ritual and symbolism, and their use may be restricted to specific contexts. In many societies, only men may play them; in others, certain drums are used only by women (as among the Venda, Sotho, and Tswana of southern Africa). Playing techniques differ widely: some drums are beaten with bare hands, others with straight or curved sticks. Friction drums are also occasionally found, such as the ingungu used in Zulu girls’ nubility rites. Except in the extreme south, drums of contrasting pitch and timbre are frequently played in ensembles, with or without other instruments, to accompany dancing. Though the role of drums is usually rhythmic, the entenga drum chime in Uganda, comprising a set of tuned drums, plays vocally derived melodies.

The body of a drum may be either bowl-shaped, tubular, or shallow-framed. Bowl-shaped drums include those made from gourds and pots as well as the small and large kettledrums found in and around Uganda. Tubular and frame drums may have either one skin or two, which are either pegged, pinned, glued, or laced onto the body. Tubular drums come in many sizes and shapes, such as cylindrical, conical, barrel-shaped, goblet-shaped, footed, and hourglass-shaped. The atumpan talking drums of the Asante are barrel-shaped with a narrow, cylindrical, open foot at the base. East African hourglass drums are single-skinned. In West Africa double-skinned hourglass drums are held under one arm, their pitch rapidly and continually changed by as much as an octave by squeezing the lacing that joins the two heads. In some areas, the wax may be applied to the center of the drum skin, and a mirliton, shells, or jingles may be attached to the body to modify the tone.

Tamak

If you’ve ever been to India, you might have heard the tamak. It’s a traditional double-headed drum played by the Santal people, and it produces a deep, rich sound that often serves as the bass for rhythmic dancing.

The tamak is made with thin metal sheets covered in cowhide and wrapped with rope. The body is sometimes deep and barrel-like and sometimes more like a shallow bowl, but the membrane stretched over the top is always tight. It’s played by striking the membrane with drumsticks.

The tamak isn’t well-known outside of India, but it has great cultural significance to the Santal people.

Kazoo

You might think of the kazoo as a wind instrument, but it’s actually a membranophone. It just looks like a flute. You play it by humming rather than blowing, and within its long, cylindrical air chamber, the oscillated air strikes a membrane and produces sound. You can also produce other sounds on the kazoo with wordless vocalizations such as “doo,” “too,” “rrr,” and “brr.”

Variations of the kazoo have existed in Africa for hundreds of years, but the first ones to resemble the modern instrument date back to America in the 1800s. Kazoo playing really took off in the 1920s with the rise of jazz bands and jug bands. It was a common staple in musicals, festivals, dance halls, and vaudeville shows.

Fun fact: The kazoo is one of the only membranophones that isn’t a drum.

Timpani

Also known as “timps” or “kettle drums,” timpani are a kind of hemispherical drum that are common in orchestras and marching bands. They have large bowls and membranes traditionally made from animal skins. Less expensive models use plastic membranes.

A distinguishing feature of the timpani is that its pitch is controlled by pedal. Pedal systems can be grouped in three categories: ratchet clutch system, friction clutch system, and balanced action system. Each system has its own pros and cons for the timpanist.

Etymologically speaking, timpani is an Italian word derived from the Latin for “hand drum,” and it’s actually plural. A single drum is called a timpano. A lot of people don’t know this and will mistakenly label multiple drums “timpanis.”

You need at least four timpani to play moderately complex music, including classic music.

Snare Drum

You’ll find snare drums on most membranophone instruments lists. They’re the most widely recognized drums in both appearance and sound, and they’re ubiquitous in rock bands, orchestras, drum lines, and more.

Why are snare drums so popular? It’s probably because they’re so distinctive. Rather than just stretching a membrane over a bowl or barrel, they place a series of stiff wires across the bottom of the drumhead. This creates a sharp staccato sound, also known as a “hiss,” which has become one of the most defining drum sounds of modern music.

Snare drums are considered essential pieces in a drum set, but you can also buy them on their own.

Bongos

A staple of Afro-Cuban music, bongos are small, open-bottomed drums that are played by hand. Players are called bongosero. Despite their fun, jaunty sounds, they’re capable of producing very complex sequences of music, including the eight-stroke pattern known as martillo or “hammer.”

You might be most familiar with bongos in the context of salsa music, but they’re also popular in everything from jazz to pop to even rock.

Bongo drums are played in pairs. While amateur sets might make both drums the same size, traditional and professional bongo sets have a larger and smaller drum, respectively called the “male” and “female.”

Djembe

Invented in West Africa, the djembe is a type of goblet drum characterized by its goblet-shaped body and animal skin membrane. Its shell is usually carved out of hardwood and decorated with strings, beads, and painted objects that are important to the player or their tribe.

The djembe has a loud, distinctive sound that can be easily heard over other instruments, making it ideal for rhythmic chants and festive dances.

Bass Drum

Also called “kick drums,” bass drums are another one that you’ll find on many membranophone instruments lists. While not as recognizable as, say, snare drums, they’re still part of your standard five-piece drum kits.

The most distinguishing feature of the bass drum is its sound. It produces deep, resonant vibrations with indefinite pitch. For this reason, bass drums are often used to mark or keep time during a musical performance. They can also create rolls, climactic single strokes, and special effect sounds meant to mimic thunder or earthquakes.

Tom-Tom

Another essential piece of 21st century drum kits, tom-toms are cylindrical drums that can be tuned to various pitches. They were originally brought to the U.S. in the 1800s by immigrants from around the globe.

There are four different types of tom-tom. The most common is the floor tom, a larger instrument with a drum shell that stands on three legs or gets attached to a cymbal stand. Other models are the rack toms, roto toms, and concert toms.

It’s believed that “tom-tom” is an onomatopoeia for the sound that’s made when striking them.

Tabla

The tabla are small twin drums played by hand. Originally hailing from India, they’ve become popular all across Asia and the Middle East, and you can find them played today everywhere from Bangladesh to Sri Lanka. The word tabla actually comes from the Arabic word tabl meaning “drum.”

As with many others on this membranophone instruments list, the tabla are considered struck membranophones according to the Hornbostel-Sachs classification.

Comb and Paper

Comb and paper is a unique handmade instrument. Like its name suggests, it’s made from just a hair comb and a sheet of paper. After the paper is folded in half and the comb is slipped inside, the player blows or vocalizes against it to trigger vibrations that create sound.

Despite its rudimentary design, comb and paper can be classified as a membranophone. It’s not unlike a kazoo in the sense that it looks like a wind instrument but is actually defined by its vibrating stretched membrane.

Comb and paper has actually been heard on the radio thanks to its usage in popular songs like “Lovely Rita” by the Beatles and “Crosstown Traffic” by Jimi Hendrix.

Tambourine

Tambourines have been around since 1700 BC, and they’ve taken many forms since then, including some that aren’t actually membranophones. For example, the jingly plastic tambourines that you played in elementary school are considered idiophones; their sounds are produced by vibrating objects, not vibrating membranes.

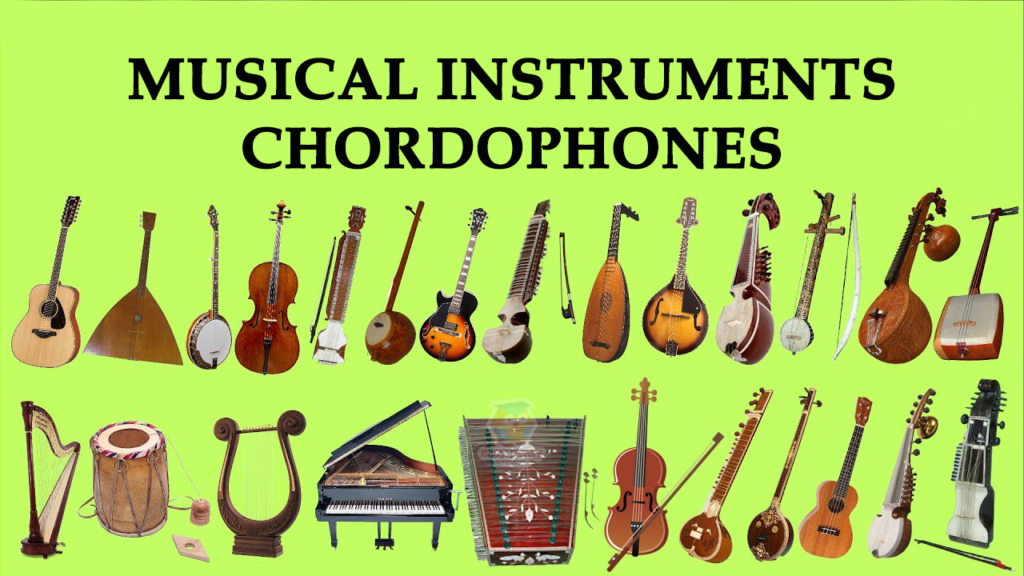

chordophones

This class, comprising instruments that produce sound from strings stretched between fixed points, is well represented in Africa. There is an abundance of specimens in the form of zithers, lutes, and harps.

Musical bows

These consist of a string stretched between the two ends of a flexible stave. There are three types: bows with a separate resonator; bows with attached resonators; and mouth bows, which use the player’s mouth for resonance. Though it is conjectural whether all varieties evolved from the shooting bow, the San of the Kalahari often convert their hunting bows to musical use. Sometimes it is held against the mouth, yielding a range of mouth-resonated harmonics, as with the jew’s harp, or it is pressed against a hollow container. Apart from adapted shooting bows, more specialized types of musical bows are widespread. Most are sounded by plucking or striking the string, but the Xhosa umrubhe is bowed with a friction stick, the xizambi of the Tsonga has serrations along the stave that are scraped with a rattle stick, and the Sotho lesiba (like the gora of the Khoekhoe) is sounded by exhaling and inhaling across a piece of quill connecting the string to the stave. Bows with more than one string are rare, but the tingle apho of the Kara people in southern Ethiopia has three.

Besides mouth-resonated bows, the gourd bow, which has an attached gourd resonator, is commonly used in southern, central, and East Africa for self-accompanied solo singing. The string is struck with a thin stick or grass stem. The Zulu ugubhu is a typical example. Harmonic tones are selectively resonated by moving the mouth of the gourd closer to or farther from the player’s chest. The fundamental pitch of the string can be altered by finger stopping; with other types, like the Swazi makhweyane, a noose or brace divides the string so as to yield two different “open” notes, and resonated harmonics are selected in the same way.

While all the above types of musical bow are simple forms of the zither, the so-called ground bow or earth bow of equatorial Africa, which has one end planted in the ground, qualifies as a ground harp.

Lutes

Characterized by strings that lie parallel to the neck, the lute is found in Africa in several varieties. The multiple-necked bow lute, or pluriarc, of central and southwestern Africa, is the oldest. This has a separate flexible neck for each string and resembles a set of musical bows fixed at one end to a sounding box. West African plucked lutes such as the konting, khalam, and the nkoni (which was noted by Ibn Baṭṭūṭah in 1353) may have originated in ancient Egypt. The khalam is claimed to be the ancestor of the banjo. Another long-necked lute is the ramkie of South Africa.

Fiddles

The bowed-lute family is represented by three types of one-string fiddle, as exemplified by the rebeclike goje of Nigeria and the spike fiddles masenqo of Ethiopia and Eritrea and endingidi of Uganda—the last being a 20th-century invention.

Harp lutes

The sophisticated kora of the Malinke people of West Africa is classified as a harp-lute. Its strings lie in two parallel ranks, rising on either side of a vertical bridge, which has a notch for each string. The long neck passes through a large hemispherical gourd resonator covered with a leather-sounding table.

Lyres

These have been termed yoke lutes, the strings running from a yoke supported by two side arms. Their distribution in Africa is confined to the northeast. In Ethiopia and Eritrea, two types occur: the large beganna, with 8 to 10 strings and a box-shaped body (corresponding to the ancient Greek kithara); and the smaller six-string krar, with a bowl-shaped body (resembling the Greek lyra). The latter type, with four to eight strings and varying in size, is also used in South Sudan, Uganda, and Kenya. The litungu is a typical specimen.

Harps

These are confined to a belt, north of the Equator, running from Uganda to Mauritania. All African harps (like those of ancient Egypt) are classed as open harps, as they have a neck and a resonator with a string holder but lack a supporting pillar to complete the triangle. In most cases, some form of buzzing device is incorporated. Examples are the ennanga (Uganda), ardin (Mauritania), kinde (Lake Chad region), and ngombi (Gabon).

Aerophones

The archaic bull-roarer (a board attached by rope to a stick and whirled about in the air) survives in various localities, notably in southern Africa among the San and neighboring peoples. Of the wind instruments proper, the three main divisions—flutes, reed pipes, and trumpets—are all well represented, though the second of these is more restricted in distribution than the others.

Flutes

At the southernmost tip of the continent, the navigator Vasco da Gama in 1497 encountered a band of Khoekhoe people “playing upon four or five flutes of reed.” Ensembles of single-note stopped flutes playing on the hocket principle, with each flute blowing its note in rotation, have been reported from various regions, ranging from southern Africa through eastern Congo (Kinshasa), Uganda, and South Sudan to southern Ethiopia. Panpipe ensembles are less common, but notable examples have been witnessed in central Africa, and particularly among the Nyungwe of Mozambique. There are many other types of open and stopped flutes—cylindrical and conical; transverse and end-blown; made from bamboo, reed, roots, stems, wood, clay, bone, and horn. Globular flutes made from small spherical gourds or from hard-shelled fruits such as Oncoba spinosa are found in southern Africa, Congo, Mozambique, Uganda, Guinea, and elsewhere. End-blown notched flutes, with a U- or V-shaped embouchure, either with or without finger holes, are widely distributed across the continent. The long Zulu umtshingo has an obliquely cut embouchure; there are no finger holes, but a double range of overblown harmonics is produced by alternately stopping and unstopping the lower end with a finger. Such instruments and many others throughout the continent are played singly, but in many areas, flutes are played in pairs or in combination with other instruments.

Reed pipes

Transverse clarinets are used throughout the West African savanna region, from Guinea to Cameroon. These are single-reed pipes made from hollow guinea corn or sorghum stems, the reed being a flap partially cut from the stem near one end. Single and double clarinets are found in southern Sudan and South Sudan among the Dinka people. Conical double-reed instruments of the oboe or shawm type have spread around the northeastern and northwestern fringes of Africa wherever Islam has taken root. Despite local variations, they are basically related to the Arab zūrnā, having a disk (or pirouette) below the reed that supports the player’s lips.

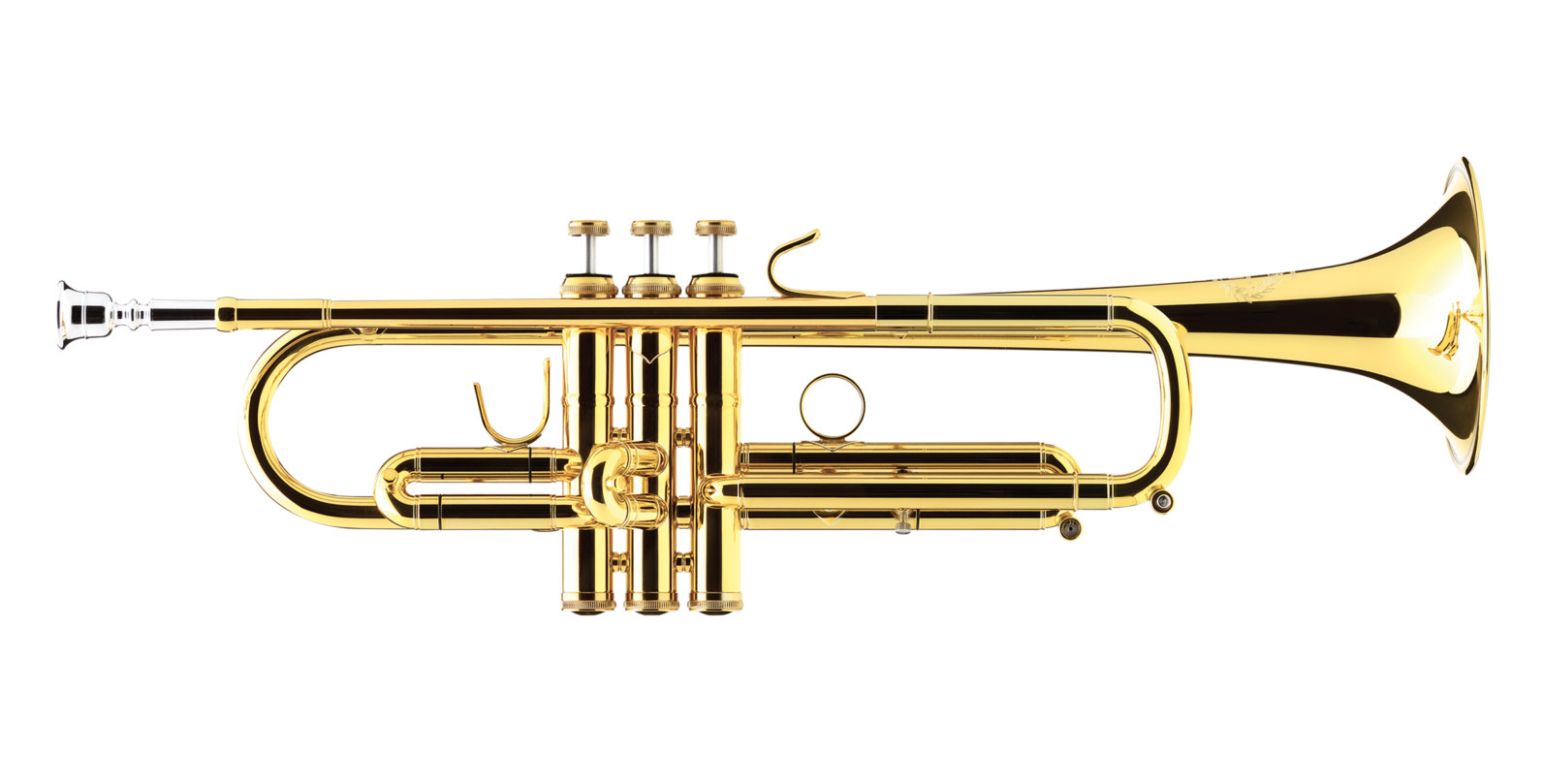

Trumpets

Lip-vibrated aerophones made from a variety of materials are widespread in Africa. Apart from musical uses, some serve for signaling. In West Africa, side-blown ivory or horn instruments may transmit verbal praises of chiefs and rulers. Among the Hausa, the long metal kakaki and wooden farai, both end-blown, fulfill this role in combination with drums. In East and Central Africa, the instruments are often made from gourds, wood, hide, horn, or a combination of these materials. In the historic kingdom of Buganda (now part of Uganda), trumpet sets were part of the royal regalia. Throughout Africa, more than one or two notes are seldom produced from a single trumpet, but trumpet ensembles are common, playing in hocket fashion.

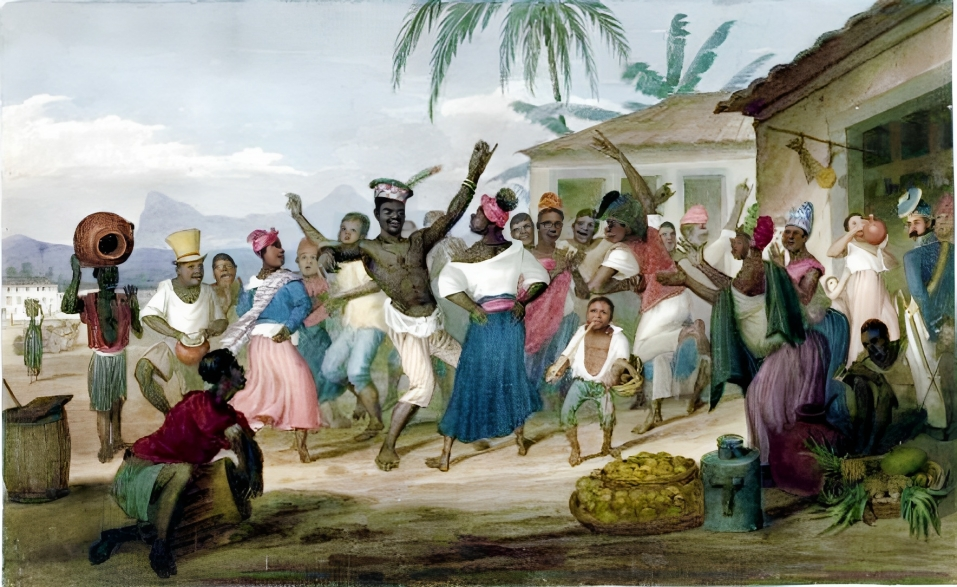

Brazilian music is one of the world’s most enjoyable cultural treasures. When most people think of Brazil, they think of sunny beaches, talented football players, beautiful people and the iconic Carnival. Carnival is, of course, admired for its vibrant costumes, exciting dance choreography, and most importantly, the hypnotic rhythmic music. Brazilians are, and always have been, great lovers of music. It is a passion that pre-dates the colonial age and can be traced back through pre-historic America and before the Portuguese first sailed along the West African coast.

This article will tell the story of an important period in world history when worlds collided, and new cultures and civilizations were formed. This is an event that has happened many times in human history; however, this time, it was recorded and coincided with an age of intellectual and cultural inquiry. The history of how Brazilian music came to be is one of wonder and beauty, as well as tragedy and sorrow. It is to be celebrated as much as commemorated because it happened and cannot be undone. It is responsible for creating music that has enriched the lives of millions of people for over 500 years and today provides the rhythm for an incredible nation and people. Read this article with an open mind, listen to all the music examples I have included with an open ear and enjoy this beautiful journey.

Brazilian music comprises styles developed in Brazil through the syncretization of African rhythmic and European harmonic, traditional styles, which formed a uniquely Brazilian sound popularly accepted by all Brazilians, regardless of their ethnic background. The primary examples of Brazilian music generes are samba, forró, axé, bossa nova, pagode, sertanejo, brega, Brazilian funk, musica popular brasileira (MPB), choro, maracuta and tropicália. However, several older genres were essential to modern Brazilian music development and will be discussed in this article.

Brazilian music, just like all of the music cultures of the Americas and Caribbean, has a history that is rich and complex. Over the years, many groups and governments have used music and the music’s authenticity to push agendas, mould society or re-shape how people perceive their history. As a result, the history of Brazilian music is largely misunderstood by most people. The modern conception of the history of Brazilian music was largely influenced by the social and political developments of the 1930s.

President Vargas’ Second Brazilian Republic was an era of ‘brasilidade’ or Brazilianization. It is an attempt to unify black, white and mixed ethnicity Brazilians under the banner of a collective Brazilian identity built around African heritage and romanticism of the Brazilian mestiço race. It resulted in a populist-nationalist movement that rejected four hundred years of European cultural domination and finally embraced African culture’s influence on the Brazilian way of life. However, The government used Afro-brazilian culture to build popular mythology for the emerging middle-class to rally around. A romanticized history of an authentic and unpolluted African musical culture, transported from the Congo to Brazil with the slaves that follows a direct linear path of evolution with some European acculturation to become modern Samba and Brazilian music as we know it today.

As you will see, this narrative is on the right track but is much too simple to explain the development of the uniquely Brazilian popular musical genres. This article will discuss the cross-cultural exchange between Africa, Portugal, and Brazil that resulted in a complex back and forth web of music being shared and borrowed, culminating in creating the unique Brazilian sound.

15 Different Types of Brazilian Musical Instruments

Music is constantly evolving, and one factor that affects that is the development of musical instruments. As time passes by, people create more instruments or improve on what they already have. Such is the case with Brazilian instruments. If you’re interested in Brazilian music, then it’s a must to familiarize yourself with the instruments used in the country.

1. Cuíca

Up first is the Cuíca, a type of friction drum that produces a very distinctive high-pitched sound. The body of this drum is made either of metal or synthetic material. Its head, made of animal skin, is about six to 10 inches in diameter. It has a bamboo stick attached to the center of the drum head and runs perpendicular to the drum’s interior.

To play Cuíca, the player holds it under one arm at chest height. The player then uses a wet cloth to rub the stick up and down. At the same time, he uses the fingers of his other hand to press on the skin of the drum near the stick. You can change the pitch depending on the pressure applied to the drum head.

The Cuíca found its place in Brazilian music as it is usually used in samba, choro, and bossa nova. This instrument is also used in folk songs, urban pop dances, and parades. You can also find a group of Cuíca players in Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival groups.

2. Bandolim

The Brazilian Bandolim evolved from the mandolin. The Portuguese colonizers were responsible for introducing this instrument to the country. The man considered a master of this instrument was Jacob do Bandolim.

The Bandolim is a small, lute-like instrument. It has a straight fretted neck, a pear-shaped body, and a flat back. Unlike traditional mandolins, Bandolims have 15 strings rather than eight. The strings are separated into five courses of triple strings for guitar tuning. They run over a floating bridge to a metal tailpiece located at the end of the body.

Bandolim is one of the primary instruments used in Choro, a popular music genre in Brazil. It is also played in dance and music festivals. Some of the virtuos Brazil has produced include Luperce Miranda and Hamilton de Holanda.

3. Pandeiro

Another percussion instrument on our list is the Pandeiro, a round-hand drum. Think of a tambourine. However, Pandeiro has a crisper tone due to the cupped metal jingles attached to the sidewall.

There are many ways to play this instrument. You hold it in one hand and use the other to strike the head to make a sound. There are also patterns you can use by using your thumb, fingertips, heel, or palm of your hand. You can also shake it or run your finger along the head.

Pandeiro has cemented its place in Brazilian music. You can find it almost always used in different Brazilian forms of music, such as samba, capoeira, and choro. In samba schools, the Pandeiro can be found in the percussion section. In other music genres, Pandeiro serves as an auxiliary instrument.

4. Alfaia

Yet another percussion instrument is the Alfaia, a wooden drum made of animal skin loosened using ropes placed on the body of the instrument. It measures between 16 and 22 inches in diameter. The drum head is clamped to the body with the help of wooden hoops.

As Alfaia is a little bulky, it has to be strapped over the shoulder. The instrument is played using a pair of wooden drumsticks. Sometimes, the stick used by the dominant hand is larger than the other one.

Alfaia is played with a technique unique to the instrument. The player holds the weak-hand drumstick in an inverted manner to produce a deep, heavy sound. This sound makes it different from other bass drums.

Alfaia is mainly used in Brazilian dances such as ciranda, coco-de-roda, and maracatu. It’s also played in Northeastern folk rhythms. Here you can see the Alfaia being played together with Agogô and other instruments.

5. Ganza

Our next instrument is the Ganzá, also known as the Brazilian rattle. This is a cylindrically shaped hand instrument made from either a hand-woven basket or a metal canister. It’s filled with pebbles, beads, or similar items to produce a sound. The metal canisters produce a louder sound.

If you’re familiar with the African calabash and Indian maracas, the Ganzá is played similarly. You simply move the instrument up and down to create sound. But in the hands of an expert, the instrument can produce complex rhythms. With the right control, the player can increase and decrease the loudness of the sound to produce variations.

This control is highly valued in pagoda and jazz-samba. In samba, the Ganzá serves as an undertone. But if played in a band, it is used to play a rhythm underneath the rest of the instruments.

6. Cavaquinho

Up next is a string instrument called the Cavaquinho. This is a small guitar-like instrument with four wires and is considered a cousin of the ukulele. In Brazil, it is called the Cavaquinho Brasileiro (Brazilian cavaquinho). Its smaller version is called the Cavaco.

The Cavaquinho is similar to a guitar in its shape and the use of metal strings. The traditional Cavaco is made with 17 to 19 frets. However, these frets are small and difficult to play. For such reason, most beginners will only use the first 3 to 5 frets. Other sophisticated Cavaquinhos have longer fretboards.

This instrument is usually played with a pick and sophisticated percussive strumming beats. It features a stronger, more prominent sound. It’s primarily because the strings are tuned to higher tension. The standard tuning of the Cavaquinho in Portugal is C, G, A, D. But in Brazil, it’s tuned D, G, B, D.

The Cavaquinho is among the most important instruments in Brazilian culture. It’s typically used in most folk music, such as choro and samba. One can also see this instrument played in festivities and carnivals.

7. Atabaque

Our list seems to be dominated by percussion instruments as we got the Atabaque next. Also known as Atabaque de Corda, this is a drum-like instrument with Afro-Brazilian origins. Traditionally, the Atabaque shell is made of Jacaranda wood from Brazil, and the head is made from calfskin. Ropes intertwine around the body and connect a metal ring at the base to the head. Wooden wedges can be found between the ring and the body. The player uses a hammer to tighten or loosen the ropes, thereby lowering or raising the pitch.

Playing Atabaque can be done in three ways. A player can use sticks, hands, or a combination of both. It’s more comfortable to play the instrument while standing. The Candomblé and Umbanda religions treat the Atabaque as a sacred instrument. Three Atabaques are often used in the Brazilian martial arts Capoeira and one in the traditional dance Maculelê.

8. Caxixi

Our next instrument on the list is the Caxixi, a percussion instrument that’s played by shaking. The body of the instrument is made of wicker woven into the shape of a bell. The bottom is made of dried gourd, and the inside contains seeds. There is a handle at the top of the bell for ease of playing.

The Caxixi is usually played alongside another Brazilian instrument, the berimbau. The player holds the Caxixi in the same hand holding the stick that strikes the berimbau. This motion shakes the Caxixi to produce a sound.

But if played on its own, the player holds the handle and shakes it in an up-and-down motion. Depending on the angle at which the Caxixi is shaken, the sound can be soft when the seeds hit the basket. The sound is loud when the seeds hit the bottom.

Before it became a secondary source for berimbau, some indigenous Brazilian Indian groups used the Caxixi for rituals. Its origins showed that the instrument was used to drive away evil spirits and summon the good ones.

9. Agogô

The Agogô is an instrument consisting of one or two bells. Arguably, this is the oldest samba instrument and is connected to the Afro-Brazilian culture. Originally, the Agogô was made from wrought iron. However, it’s now produced using metals of all shapes and sizes to create different sounds. The Agogô usually comes with two metallic bells in the shape of a U. The smaller bell is held higher than, the larger bell.

The instrument can be played in two ways. One, you hit the bell using a wooden stick to produce a cowbell-like sound. Two, you squeeze the bells together to create a clicking sound.

Like the Caxixi, the Agogô is played alongside the berimbau in capoeira. It is also played in religious activities such as candomblé. Not only that. the Agogô is a staple in samba baterias or percussion ensembles.

10. Berimbau

One of the most common traditional instruments in Brazil is the Berimbau. This is a single-stringed percussion instrument popular in the Afro-Brazilian community. The Berimbau consists of the following parts: verga, cabaça, arame, dobrão, and baqueta. Verga is the wooden bow, traditionally made of biribá wood, that grows in Brazil. The bow is four to five feet with a steel string (arame) tied from one end of the bow to the other.

The cabaça is the gourd resonator with a big opening. The baqueta is the stick used to play the Berimbau, while the dobrão is a coin or stone used to stop the string. The Berimbau is popularly known for accompanying the game dance capoeira. The faster Berimbau is played, the faster the capoeira player moves. The instrument is also an important part of the Candomblé-de-caboclo tradition.

11. Repinique

The Repinique is another common instrument used in samba baterias. It’s almost always used in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro Carnival baterias, as well as the Bahia baterias (where it’s called Repique).

The Repinique consists of a metal body and a nylon head tightened with metal tuning rods. Like the Alfaia, the Repinique is carried with a shoulder strap attached to a tuning rod. In Bahia-style samba, The Repinique is played with two wooden sticks. In Rio, it’s played with only one.

The Repinique is quite similar to the tenor drum used in marching bands and the tom drum. As a lead instrument, it alerts the rest of the bateria of rhythmic changes. In samba, it guides the dancer to keep the tempo and rhythm. These days, you can find this instrument in soccer or football matches. It is used along with other percussion groups to incite excitement.

12. Reco-reco

Up next is a scraper percussion instrument. The Reco-reco, also known as the querequexé or the caracaxá, is often used in Brazilian music. Traditionally, the Reco-reco was made from bamboo or wood and played with a wooden stick. It consisted of a sawtooth-notched cylindrical body with strings attached.

Modern Reco-reco now features a metallic body, resulting in a louder, echoing sound. The resonator is made from sheet metal with spring coils attached. It’s also played with a metal stick rather than a wooden stick.

To produce a sound, the player uses the metal rod to brush up and down the spring coils. What comes out is a scrapping sound amplified by the resonator. The Reco-reco has long been used to accompany capoeira, rural dances, and samba. It also serves as an auxiliary instrument.

13. Tamborim

The Tamborim is a super-small Brazilian frame drum that is no more than six inches in length and is typically made of wood, plastic, or metal. It is often mistaken for the common tambourine. However, unlike the tambourine, the Tamborim doesn’t have snares or jingles.

In most parts of Brazil, the Tamborim is played with a small wooden drumstick. In samba-batucada, it’s played with a beater made of plastic or nylon threads bound at the end using tape. The Tamborim is rarely played by hand.

This instrument is used in a myriad of Brazilian music genres, including samba, bossa nova, chorinho, and pagode. It’s also used in cucumbi, a northeastern folklore rhythm. In commercial music genres, the Tamborim serves as an auxiliary instrument.

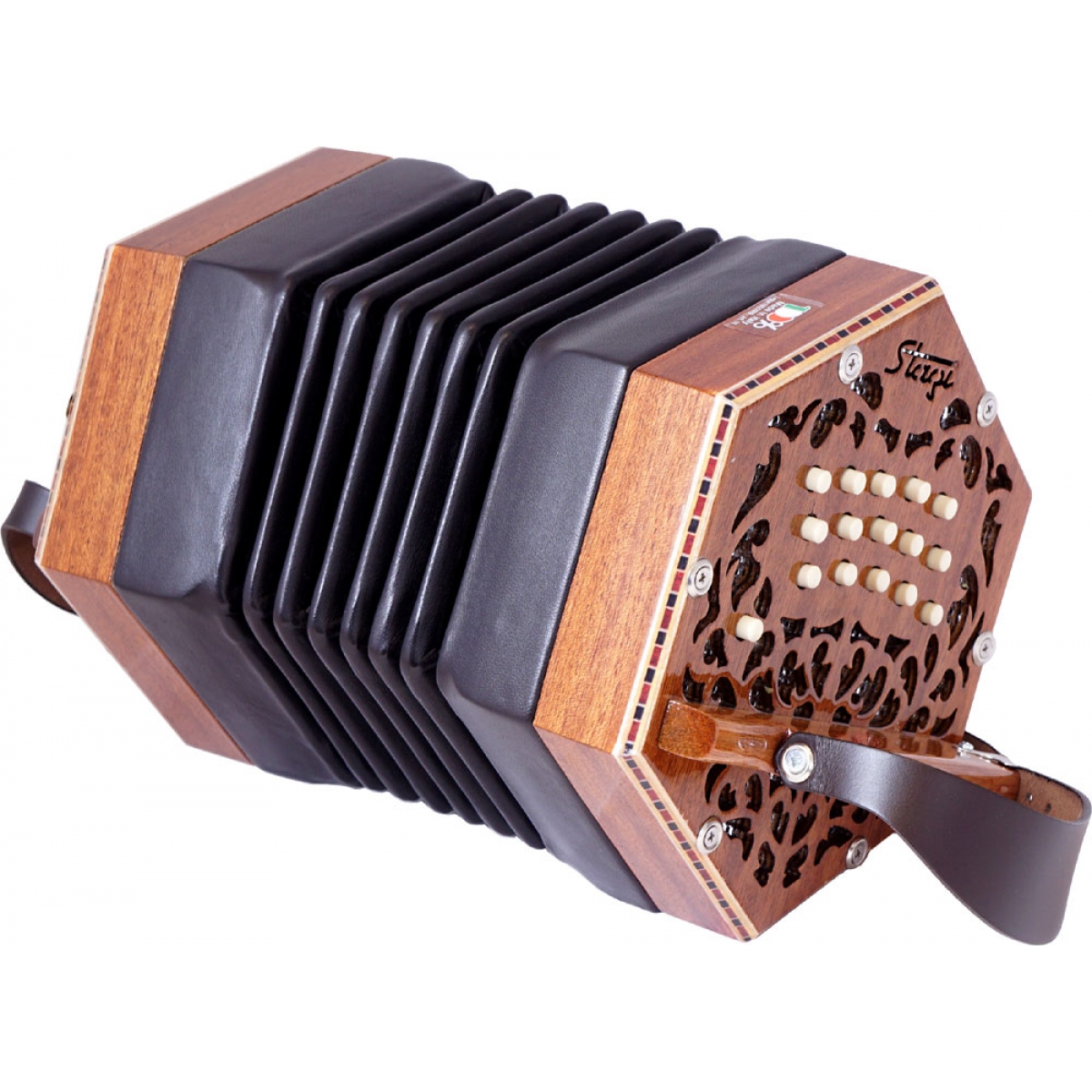

14. Accordion

Up next is the Accordion, popular in southern and northeastern Brazil. The Portuguese brought the instrument to the country in the 19th century. Notably, it became the Rio Grande do Sul state’s official symbol instrument.

In some parts of Brazil, the Accordion serves as the main instrument in many styles of Forró and Sertanejo. Forró is a musical genre popular in the northeastern region of Brazil. Sertanejo, on the other hand, is a musical style that came from the Midwest and southeast Brazil.

Not only that. The Accordion is a principal instrument in Junina music of the São João Festival. Several notable Brazilian accordionists include José Domingos de Morais and Mestrinho. The video above shows Mestrinho with another Brazilian musician.

15. Saxophone

One notable addition to the array of Brazilian musical instruments is the Saxophone. Heitor Villa-Lobos, the foremost representative of concerto music, played a key role in popularizing this instrument in Brazil.

His renowned work, “Fantasia for Soprano Saxophone and Orchestra,” remains a cornerstone of the Brazilian Saxophone repertoire and has inspired countless young musicians to learn and embrace the instrument.

From street performers to bossa nova compositions, the Saxophone continues to be a prevalent feature of Brazil’s music scene, adding a jazzy, bohemian vibe to performances and enriching the melodies with its unique sound. Even today, it remains a beloved and important instrument in Brazil’s rich musical tradition.

“The world by day is like European music; a flowing concourse of vast harmony, composed of concord and discord and many disconnected fragments.”

Rabindranath Tagore, Bengali poet, writer, composer

Nothing speaks to the soul like music – and nothing to the soul of European inventiveness like its orchestra of musical instruments. Whether you’re listening to a classical symphony or a Magyar marriage, on a Slovakian hillside or a Hawaiian beach, whether you want to pluck or blow, you can bet there’s a European instrument that can provide the perfect accompaniment. What links an Icelandic warrior, a Copenhagen virgin and a slab of butter? What do you do with music that can no longer be played? Where in Europe would you beat out a rhythm with a devilish do-it-yourself pole? What’s the best way to drown out a yodeller? Find out below with our guide to the musical instruments from across all of Europe.

Portugal

Ukulele

Portugal’s most famous musical invention took root almost on the other side of the world: 12,000 kilometres away, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. In the late 19th century, Joao Fernandez went to Hawaii, clutching a small lute-like instrument known variously as the cavaquinho, the branguinha or the machete de braga. The locals were thrilled with this compact means of accompaniment – and renamed the four-stringed instrument the ukulele, “jumping flea”. The instrument, originally from the Portuguese island of Madeira off the coast of Africa, is now more associated with tropical Hawaiian ballads. The banjolele, a hybrid which incorporates features of the banjo, was made famous by the films of 1940s British comedian George Formby.

Spain

Guitar

Spain’s claim to musical fame is one that has virtually taken over modern music. The acoustic guitar as we know it probably came from Spain in the early 16th century, a straightforward way to pluck chords to accompany the human voice or set out a rhythm for dancing. Once relying on its own hollow resonant body to amplify sound, the modern electric instrument merely has a flat panel with magnetic pickups and a cable socket. Easy to play, transport and amplify, they have become the quintessential staple of modern pop music for the last sixty years or more.

France

Oboe

The oboe, one of the four woodwind instruments of the classical orchestra, gets its name from the French “hautbois,” or “high wood,” and seems to have originated in mid-17th century France; Louis XIV was said to be a major fan. Unlike the clarinet, it uses a double reed to generate a sound from the player’s breath; its bright, strong sound can produce a full and lovely timbre (though it can also sound not unlike the quack of a duck). So piercing is it, that it traditionally plays the A to which all other instruments listen and tune at the beginning of a concert; but the method of producing sound makes it one of the most difficult orchestral instruments to master. (Only the French horn — which, by the way, isn’t really French — is said to be harder). Few can play the instrument with the virtuosity or straightforwardness of a clarinet or saxophone: probably why it has little taken off as an instrument in jazz or pop music.

Iceland

Langspil

Belonging to the zither family, the langspil was brought from northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Relatives such as the mountain dulcimer are found in Pennsylvania, USA, brought by German settlers. There is no single way of constructing a langspil, but a typical one will have two “drone” strings, which play a single continuous note, while a third often fretted higher string allows a melody to be plucked, bowed or hammered, while the instrument itself sits across the seated player’s lap.

Ireland

Bodhrán

The bodhrán (bow-ron) is a kind of round drum, related to the tambourine, which provides the rhythm for a traditional Irish jig or reel, alongside other instruments such as the flute, concertina and fiddle. Traditionally, it is made from a ring of willow or rosewood, with a membrane of goatskin or sheepskin – though these days artificial alternatives are often used. The instrument is laid on the seated player’s knee and struck with a small double-sided stick, known as a beater or tipper, that allows the player the freedom to make a wide variety of sounds. The player’s other hand sits inside the head of the drum, and by brushing across different areas of the skin can create a wide variety of tones, pitch and resonance.

United Kingdom

Concertina

This versatile and compact means of accompaniment was invented in London by Charles Wheatstone around 1829 (though similar designs were being developed in parallel in Germany). Another reed instrument, this one generates air not by breath, but by pulling the central section in and out like a bellows. In the original English concertina, the pitch is changed by four rows of buttons at each end, allowing the player to play all 12 notes of the conventional chromatic scale with facility. Scientist Michael Faraday used the instrument to demonstrate the physics of sound; Lord Balfour, briefly Prime Minister in the early twentieth century, was a keen player. Though the instrument had some limited take-up in classical music, it is now most used in English and Irish folk music.

Norway

Hardanger Fiddle

Norwegians are well known for wanting to do things differently! For them, the traditional four-stringed violin just wasn’t good enough to do justice to traditional dances like the gangar, halling or springar – so they had to add four or five more. Even more confusingly, the extra strings on the Hardanger fiddle – named after a region of western Norway – are not touched by the player’s bow, but sit below, “sympathetically” resonating when they hear a sound they like. That – combined with a flat bridge enabling two strings to be bowed at once – makes it easy for even the solo player to be heard over the sound of festivities and clomping feet. Traditionally the Hardanger fiddle is made from local materials like cow-horn, spruce, maple and applewood, with decorative patterns like rose designs painted onto the body, and mother of pearl used to adorn its edges. A wave of Nordic migration to the USA in the mid-19th century means many of the instruments are still found and played across the pond.

Sweden

Nyckelharpa

The Swedes wanted to outdo their Nordic neighbours and added, not just extra strings – but also a whole keyboard. The instrument appears to have arrived in Germany, and it is related to the hurdy-gurdy. Though the sound of the nyckelharpa (“key fiddle”) is still made from a traditional horsehair bow, different notes are made not by stopping the string with the left hand, but by pressing keys found alongside the neck. As well as bowed and sympathetic strings, there is also often a drone string, which can produce a continuous low pitch to accompany the flightier melody. Unlike the violin, it is often played horizontally, with a strap passing around the player’s shoulders, rather like a guitar.

Finland

Kantele

The Finnish kantele appears to be descended from the Arabic qānūn, which reached Europe in the 12th century. Related to the zither, the strings – as many as 35! – are stretched across a frame which has no neck, and plucked. While mainly associated with local folk music, you can also hear a Finnish kantele accompanying the lullaby All Is Found in the Disney film Frozen 2.

Denmark

Lur

Archaeologists first found these curious cast-iron horn instruments at the end of the eighteenth century, and many more have been found since, principally in Denmark but also elsewhere in Scandinavia; most remarkably of all, despite being over 3000 years old, some of them can still be played. The specimens were originally identified with the lur, referred to in Icelandic myths as summoning warriors to battle, though they may also have been used to put people into a trance for religious ceremonies. Musically the instrument is fairly simple, with harmonics enabling a player to produce between 8 and 12 rich and sonorous notes; they often also have an ornamental plate, decorated with a dozen or so depressions. Danes have been keen to identify with this token of their proud warrior past; two entwined lurs decorate the logo of the country’s leading brand of butter – known, of course, as Lurpak. In Copenhagen’s central square opposite the city hall sits a bronze statue of two lur-blowers who, legend has it, will sound their instruments should a virgin ever happen to walk past.

Netherlands

Double-keyed Harpsichord

This mainstay of 17th-century baroque music was not invented in the Netherlands, but the country has a decent claim to one of the instrument’s most famous proponents. Instrument maker Hans Ruckers the Elder was born in 1555 in Mechelen, and later lived in Antwerp, both in modern-day Belgium. He built many of the best and most beautiful harpsichords, many of which lasted for centuries, undergoing multiple refurbishments and overhauls. The harpsichord is a versatile harmonic instrument, heard accompanying virtually all seventeenth-century ensemble works such as those by Purcell, Bach or Handel; though, because the strings are plucked rather than hammered, the instrument does not have the dynamic and emotional range of the piano which eventually supplanted it. Ruckers’ most famous innovation was to add a second keyboard, often tuned a perfect fourth apart from the first, allowing the player to rapidly transpose into a different key.

Belgium

Saxophone

Belgium lays claim to one of the few instruments not just invented by a single individual but named after him. Adolphe Sax was born in the French-speaking city of Dinant in 1814 before the country of Belgium even existed. A player of the clarinet and other woodwind instruments, he studied at the Brussels Conservatoire. After experimenting with numerous inventions including an organ and a sound reflection screen he finally presented his masterwork, the saxophone, intended to combine the powerful sound of brass instruments like the trumpet with the versatility of woodwind. Saxophones exist in multiple types, including higher-pitched sopranos and altos, and deeper tenors and baritones, but the orchestra consisting solely of different kinds of saxophone never really took off. Classical composers including Britten and Glazunov wrote for the saxophone as an orchestral or solo instrument, but it took off in the jazz bands of 20th century America, reaching a zenith in the virtuosity of players like Charlie Parker and John Coltrane.

Germany

Tuba

The chunkiest member of the brass family was patented by Johann Moritz and Wilhelm Wieprecht in Berlin in 1835. While frequently used in the classical orchestra, they are also associated with marching and military bands (the latter of which Wieprecht directed): largely as they are portable, at least relative to instruments of comparable pitch such as the double bass. Another German instrument, the Wagner tuba, was invented by the composer some twenty years later, as he looked for an instrument to bridge the wide variety in the brass section and do justice to the arrival of the Gods at Valhalla in his opera Das Rheingold.

Austria

Arpeggione

On your tour of Europe, spare a thought for the musical might-have-been: the instrumental innovations that nearly made it, the bright ideas that just couldn’t bridge the gap. Such is the fate of the arpeggione, invented in 1823 by Johann Stauffer in Vienna. While tuned and fretted like a guitar, the hybrid instrument was placed between the knees to be bowed like a cello, with strings set so as to make it easier to play two notes at once. Alas, this arrangement proved too unwieldy for the good folk of Vienna to manage and the sound was nothing special, so after a brief flash of trendiness the arpeggione found itself on Queer Street. The only reason people still mention the instrument is that, during its brief heyday, Franz Schubert composed a work with piano accompaniment. Unfortunately, he didn’t circulate the sonata right away: by the 1870s, when it was published after his death, few people could even get their hands on something to play it on. Today, although still known as the Arpeggione Sonata, the work is usually played on the cello or viola.

Switzerland

Alphorn

What is a lonely Alpine shepherd to do, with only his flock and the tall pine trees of the forest for company? Why, build an alphorn, of course! Originally referred to in writing in the 16th century, this enormous instrument has long been bellowed across the valleys to summon creatures of all kinds – the cows in for milking, and the faithful to prayer. Unlike the woodwind instruments made out of metal, this one is made out of wood – its length and pitch traditionally depend on the height of the tree used to make it – but is generally considered a brass instrument due to its sonorous tone quality. Now cheerfully reinvented for tourists as perhaps the most effective way to drown out the sound of yodelling, the alphorn is now often made out of ash wood or even carbon fibre.

Italy

Piano

The Boot can lay claim to several extremely important instruments. The two earliest recorded violin makers, the 16th century Andre Amati and Gasparo di Bertolotti, worked in Cremona and Brescia, setting the model for the modern instrument. But Italy’s crown must surely go to classical music’s versatile if heaviest, instrument. Though the piano contains many innovative features, it was invented by a single person, Bartolomeo Cristofori, in Florence around 1700. He was bored of making harpsichords which, though a nearly universal means of accompaniment, could not sustain sound, nor play at different volumes. Cristofori ingeniously set about fixing those problems one by one, replacing plucking plectrums with striking hammers, introducing an escapement allowing the hammer to fall away and not dull the sound, a check to stop hammers bouncing back against the string, and a set of dampers to stop strings not in use from resonating. With Germanic rigour, Cristofori named his instrument the clavicembalo col piano e forte – a “harpsichord with soft and loud”. The astonishing invention found little take-up in his home country or during his lifetime, but news of it spread to Germany where it eventually caught on. Around 1830, a number of technological innovations were made allowing strings to be set at higher tension, with iron frames and hammers tipped with felt, not leather. Instruments before that date are now normally called fortepianos, and more modern ones pianofortes.

Czechia

Vozembouch

In Czechia, when it comes to musical instruments, they believe in do-it-yourself. The vozembouch (“stamp on the ground”) does what it says on the tin: but apart from this consistent manner of playing, each instrument is as unique as its owner. Originally it was a single-string fiddle, bowed with horsehair and with an animal’s bladder operating to aid resonance. Nowadays it functions as a percussion instrument, consisting of a vertical stick about 1 metre high, often of beechwood, to which a variety of objects are stuck: small snare drums, cymbals, bells, rattles, ribbons, tin cans, tambourines, bottlecaps, washboards, you name it. All this is topped off by a decorative wooden head, often depicting the devil. Neither standardized nor mass-produced, as long as it looks impressive and sounds OK, there are few rules to constructing your own vozembouch.

Slovakia

Fujara

In Slovakia, bigger is better. This mammoth “bass flute” is as tall as a man: sometimes even over 2 metres long. So long, in fact, that the player cannot usually stretch from the fingerholes while blowing into the top: so must use an extension pipe which allows them to blow into an opening closer to the middle of the instrument. A traditional fujara is made out of elder wood aged for 3 years, and decorated with designs particular to the maker. As it only has three fingerholes, the player must also change the pitch by contorting the mouth to make harmonics, just like a trumpeter. Originally an instrument of shepherds, the fujara has now become a symbol of national pride: declared an element of humanity’s intangible heritage by UNESCO in 2008, it is the perfect accompaniment to a song celebrating the derring-do of the 18th-century outlaw hero Juraj Jánošík – or just a lament to the travails of being a lonely shepherd.

Poland

Koza

Poland’s most famous instrument is a kind of bagpipe, in which air held in a sack is squeezed to make a sound while the player changes the pitch by moving fingers on a recorder-like chanter; a separate drone pipe makes a continuously pitched sound to accompany the melody. They are popular in countries that were formerly associated with the Austro-Hungarian empire, including modern-day Hungary, Poland, Belarus and the Balkans. In Polish, Koza means “goat,” the animal skinned to make the bag. The goat’s fur is often still attached and a small carving of the animal is displayed; those made from black goats are known as kozioł weselny and traditionally played at weddings.

Estonia – Latvia – Lithuania

Kokle (LV) Kannel (EE) Kanklės (LT)

These instruments, known collectively as the Baltic psaltery, are similar to the Finnish kantele; in the case of the Estonian kannel, it is s bowed rather than plucked. For the Lithuanians, the kanklės have a morbid association: they believe a true instrument can only gain its sonorous soul if the wood is cut on the day of the death of a loved one; playing it is a spiritual act akin to meditation. In Latvia, the strings of the kokle do not sit on a bridge, making the sound quieter but richer.

Belarus

Surma

The Surna, also known as the Belarusian trumpet, is a wind mouthpiece musical instrument, the first pictures of which can be found in Belarusian documents of the 13th century. Alongside straight trumpets, they were curved ones, sometimes they were covered with birch bark. The trumpet was mostly used during warfare as a signal instrument. The everyday life of medieval knights in times of war can’t be imagined without this instrument.

Ukraine

Trembita

All the ladies want to know — who has the longest? And the Ukrainians are willing to tell you. The trembita, a kind of mountain horn, is said to be the longest musical instrument in the world, extending to as much as eight metres. And it’s long in terms of time too: the ideal instrument is hewn from a fir tree aged over 120 years — ideally one that has been struck by lightning to assure you the right trumpet-like tone. Invented by the Hutsul people of the Carpathian mountains, the trembita is a means of communicating across the wide valleys, letting those on neighbouring hillsides know of death, births, weddings or wars, or simply the forthcoming arrival of a flock of sheep.

Romania – Moldova

Nai

The traditional Romanian folk troupe has a violin, the lute-like cobza, and the nai panpipes, sometimes with a drum or double bass added for good measure. A modern nai consists of over 20 notes spanning three octaves, made out of bamboo. Unlike the South American panpipe, the tubes of the nai are arranged not in a straight line, but in a curve, allowing players to reach each of the pipes just by turning their heads. The different pipes also vary in diameter as well as length, allowing a more consistent tone as the player travels up and down in pitch.

Hungary

Ceglédi Kanna

In Hungary, they are resourceful when it comes to making music, and a principal tool of Romany folk musicians is… the water jug. Traditionally coming from the town of Cegléd, just to the southeast of Budapest, the Ceglédi kanna designed in the twentieth century is a metal container originally intended to hold a good few litres of water. Thanks to its distinctive shape, including an angled handle, cylindrical spout, and narrow rim, the player can create a variety of percussive, rhythmic sounds by striking it with either hand, as it lies balanced between the seated legs. We cannot confirm rumours that the hard-working and thirsty musician might fill it up with something stronger than water.

Slovenia – Croatia – Serbia – Montenegro

Tamburica

The Tamburica is a lutelike instrument with a long neck found across the Balkan region and in Hungary, plucked in traditional folk music. It appears related to the Persian tambour, arriving in the region via the Ottoman occupation or via Greece. Frets can be moved allowing the instrument to be played in multiple different kinds of scales; the exact tuning differs, but often are tuned in pairs allowing the player to rapidly repeat the same note like a mandolin.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Diple

The diple, also known as the mih, started life as a bagpipe; but they got rid of the bag, and just left the pipe, leaving an instrument somewhat like a recorder. While there is no drone note, the chanter features two bores drilled into a single piece of wood, one of which has six holes and the other two, each of which has a clarinet-style reed at the end. This allows the player to produce two notes at once: Shepherds or wedding entertainers can thus get two for the price of one. The instrument is often made out of Maplewood, with elements in cow-horn or tin.

Kosovo – Albania

Ocarina

One of the oldest instruments in Europe, older even than the Danish lur, belongs to one of its youngest countries. Half a century ago, in the village of Runik in the Drenica Valley, an ocarina estimated to be between five and eight millennia old. Just eight centimetres tall with finger holes and a mouthpiece, this instrument could have been delighting a local shepherd or his flock long before recorded history or the building of the Egyptian pyramids.

Bulgaria – North Macedonia

Kaba Gaida

The local variety of bagpipe is the pride of the Bulgars! And particularly the low-pitched kaba Gaida, which features a chanter which is both hexagonal and curved at the end. The reed is made of elder wood, gathered in the coldest pet of winter and aged for several years.

Greece

Bouzouki

This member of the lute family shows Greece as a cultural crossroads: it is an import from Turkey adapted using Italian techniques. Like the mandolin, the instrument has strings in consistently pitched pairs allowing the player to rapidly repeat notes. Traditionally there were three pairs of strings, while more recent bouzoukis have four, plucked with a plectrum. The instrument is ubiquitous in Greek pop and folk music, often accompanied by its little brother the baglamas, the kithara (guitar), a violin, an accordion, or a piano.

Cyprus

Laouto

Unlike the oud and other short-necked lutes, the laouto has a higher string tension due to its longer neck and hence is brighter in tone than the oud. It is a long-neck fretted instrument of the lute family, found in Greece and Cyprus. The role of the laouto in traditional music is primarily that of accompaniment. The laouto is often played in a duo (the one laouto tuned more bass than the other) with the Cretan lyra or with the violin (in Cyprus).

Turkey

Kemençe

The phenomenal instrument and almost symbolic icon of the Black Sea region is a three-string traditional folk instrument played with the help of a bow. In order not to be confused with the classical violin in Western music, the instrument in question is called the Black Sea fiddle. The style of work differs from other cultures by being played very actively and accompanied by a dance.

Pakistani music, as diverse as its multiethnic population, ranges from qawwali, a popular brand of music branched from Sufi Islam, to good old-fashioned rock ‘n’ roll. It includes diverse elements ranging from music from various parts of South Asia as well as Central Asian, Persian, Turkish, Arabic, and modern-day Western popular music influences. With these multiple influences, a distinctive Pakistani sound has been formed. From Pakistan’s inception, music was a form of entertainment like anywhere else. But unlike Pakistan’s hardline-Islamist image today, society was just a little bit different back then.

In the 1960s, Pakistan, a place where alcohol was still legal and couples frequented movie theatres hand-in-hand, prospered, and visits from Jackie Kennedy probably helped too. The ’70s and ’80s saw the rise of political Islam, culminating in the conservative dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq. Despite this erratic political landscape, the tradition of Pakistani music remained strong.

Today, I will take you on a tour of Pakistan’s music since gaining independence on August 14, 1947.

1940s:

Alam Lohar is a classic cult Punjabi-folk favorite. Born in 1928, Lohar began his career when he was just a teenager. Listen closely and you’ll realize why he is considered to be (metaphorically speaking, of course) the grandfather of Punjabi MC, today’s biggest bhangra music star. Using a peculiar instrument called the Chimta and an overwhelming singing stamina, Lohar wooed the crowd with the song Jugni, below:

1950s:

With a few exceptions, minorities in Pakistan appeared frequently on TV during the 1950s, singing some of the great music to come out of the entertainment industry. Sunny Benjamin John and Irene Perveen, singers belonging to Christian families, stole the hearts of young Pakistanis with their heartfelt music, their music falling into the ever-popular and favorite genre of ghazals, songs of poetic expression. Also, hello color-TV:

1960s:

Ah, the golden years of Pakistan. Music in the ’60s took a turn around the world. With the Beatles in the West, Pakistan produced Ahmed Rushdi in the East – arguably, the first disco star of his generation. Ko-ko-Korina, a song that earned a Platinum Jubilee, was so popular in the region that it escalated the Pakistani movie industry to great heights. Many renditions of the song appeared in the next few decades both domestically and in Pakistan’s next-door neighbor, India. Folks put your dancing shoes on:

1970s:

The 1970s gave rise to a popular, risqué trend called the “hair dance.” Young Pakistanis who attended dance parties were no strangers to this style of dancing. To do the hair dance, one had to shed all their inhibitions and shake it, literally. The video is pretty self-explanatory:

1980s:

To any Pakistani who grew up in the ’80s, the words “Vital Signs” were not measures of various physiological statistics, but a musical band of heartthrobs who sang Dil Dil Pakistan, literally meaning Heart Heart Pakistan. These young, leather-jacket-wearing-motorbike-riding men were patriotic, and Pakistanis realized, “You know what? It’s cool to be Pakistani.” Styled in Ray-Ban wayfarers, the band members of Vital Signs challenged General Zia-ul-Haq’s strict regime and introduced Pakistanis to the world of pop music. Because it was a patriotic song, it remained uncensored. Earlier in the decade, the late Nazia Hassan sang Disco Deewane, or Crazy about Disco, a song that plummeted to the US Billboard charts, a first for any Pakistani singer. Because the 80s produced some of Pakistan’s most memorable pop stars, you get to enjoy not one but two videos:

1990s:

The U2 of Pakistan, Junoon struggled with promoting their music. The US invasion of Afghanistan left much violence on the streets of Pakistan and thus began a long, ongoing stretch of political instability. One band member, Salman Ahmed, said he made his first political statement by creating a rock band. Junoon’s music, which highlighted the corruption of Pakistan’s elite (Benazir Bhutto, for instance), got them into trouble. They were banned. Junoon vocalist Ali Azmat considered himself and the band to be “musical guerillas,” but the ban only gained in popularity as counter-culture heroes.

ALGHOZA

This instrument consists of a pair of flutes of nearly the same length and width. One flute is used for a continuous drone, while the other is played to produce a melody. The alghoza has six holes.

The alghoza originated in Sindh, but its popularity has spread all over Pakistan. Many of the tunes presented on this instrument are composed in the raga Bheem Pilasi, which is sung soon after sunset. Bheem Pilasi emanates a romantic mood and is an intense expression of longing and waiting for the beloved.

BANSURI

The bansuri, or flute, is one of the most primitive instruments in Pakistan. It is played by holding it horizontally against the lips. It has six holes, which are closed and opened with the finger-pads in accordance with the melodic phrases. The thumb below supports the flute. The typical flute has a slanting mouthpiece that can easily rest between lips. The notes of the higher register are produced by accurately controlling the apertures and by contracting the lips to blow a narrow stream of air.

Sain Allah Ditta Qadri is known for his flute playing, and Salamat Hussain is a meritorious flutist who has won the President’s Pride of Performance medal.

CHIMTA

The chimta is a pair of fire tongs still used in Pakistani homes. The chimta used by performers is approximately one meter long. It is played by hitting the tongs against each other and slapping a large iron ring at the bottom against the tongs. Popular in Punjab and Sindh, it is used mostly as an accompaniment to folk and mystic songs.

DHOL

The Dhol or drum, which means “lover” in some regional languages, is a rhythm instrument enjoying wide popularity in both town and countryside.

The Dhol was originally used for communication over long distances for community announcements and to summon congregations. Today, the instrument is played on a variety of occasions, such as folk festivals, dances, horse and catel shows, rural sports, wrestling matches, weddings, etc.

The Dhol is a two-headed, hollowed-out piece of wood covered with goat skin. It is beaten with wooden sticks and is certainly an instrument of great antiquity.

GHARA

The Ghara of Punjab (dilu or changer in Sindh, many in NWFP, and not in Kashmir) is actually a baked clay pitcher normally used for storing drinking water. Used to produce a fast rhythm, it is one of the most primitive percussion instruments known.

The height of a ghara ranges from 30 to 35 centimeters, with a girth of 80 to 90 centimeters. The diameter of the mouth is 8 to 10 centimeters. A metallic ghara is known as a gagar or matki. The performer sits on the floor, places the instrument in front of his knees or on his lap with its mouth up, and beats the side wall with the fingers of the right hand while the left-hand strikes the mouth to produce a stronger ground beat.

Ghara is also used by village people as a float for swimming. The swimmer holds the hollow pot under the belly, its mouth down, and swims across a river or stream. A popular folk song of Punjab takes its name from the ghara. It is associated with the romantic folk tale of Sohni and Mahinwal. Sohni used a garha to swim across the river Chenab.

HARMONIUM

The harmonium is a keyboard instrument. Thin metal tongues vibrate to a steady current of air produced by pumping the bellows. The harmonium has a three-octave keyboard.